Alzheimer’s isn’t Just for Boomers Anymore

Blue Cross/Blue Shield reports a 200% increase in Dementia/Alzheimer’s in the younger set

According to the Blue Cross/Blue Shield Human Health Index:

‘Early onset dementia and Alzheimer’s disease affects a growing number of younger commercially insured Americans. In 2017, about 131,000 people between the ages of 30 and 64 were diagnosed with either form of dementia. Diagnosis rates increased by 200% from 2013-2017 in ages 30 to 64. The average age of someone in the commercially insured population living with either condition is 49, and women are disproportionately impacted more than men.”

In 2014, 4.2 per 10,000 adults (age 30-64, average age 49) were diagnosed with early-onset dementia and Alzheimer’s disease compared to only 3 years later, when in 2017 the number was 12.6 per 10,000 adults.

Lifetime risk for Alzheimer’s

- 1 in 5 for women

- 1 in 10 for men

Why women may be more prone to Alzheimer’s than men may be their immune system working overtime.

Women are more likely to have an autoimmune disease compared to men. Some research points to amyloid beta peptide (a precursor to amyloid plaques), present in Alzheimer’s patients as the culprit. By acting as a protection against invading infections in the brain, (women are more prone to hyperimmune responses, thereby causing an overactive immune response to invading bacteria and fungi) amyloid plaque builds up, causing Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Possible risk factors for early-onset Alzheimer’s include:

- Excessive alcohol use

- Social isolation

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Genetic predisposition

What is amyloid plaque?

Amyloid plaque is a buildup of abnormal amyloid beta proteins that form in the spaces between nerve cells. (for Alzheier patients, these are present in the spaces between nerve cells) These proteins form amyloid fibrils. It is believed that these fibrils interrupt communication between neurons, causing Alzheimer’s, and can play a part in the development of Lewy body dementia. Amyloid fibrils lead to a group of diseases called amyloidosis. Amyloidosis can affect more than just the brain. It also is known to collect in other organs and tissues in the body, such as the heart, liver, and skin, and if left untreated, can be lethal. (1)

Alzheimer’s is also known as type 3 diabetes

Type 3 diabetes occurs when neurons in the brain become unable to respond to insulin, leading to insulin resistance in the brain. Persons with type 2 diabetes have an increased risk of Alzheimer’s dementia by 45-90%. (2)

The shocking fact is that Alzheimer’s is fast becoming a disease affecting even middle-aged adults.

Risk factors/causes of Alzheimer’s diseases

The exact mechanisms in which the amyloid plaques build up leading to Alzheimer’s disease are not known, however, some factors may contribute to the process.

Genetic factors

According to The Alzheimer’s Association research shows that those who have a parent or a sibling with Alzheimer’s are more likely to develop the disease than those who do not have a first-degree relative with Alzheimer’s. Those who have more than one first-degree relative with Alzheimer’s are at an even higher risk.

Age

The greatest known risk factor for Alzheimer’s and other dementia is increasing age. While age increases risk, it is not a direct cause of Alzheimer's.

Environmental factors

Diet and inflammation are known risk factors that set the body up to develop the amyloid plaque found in the brain.

If you already have amyloid plaque forming, either through genetics, inflammation from stress, or have type 2 diabetes, you are at a high risk of Alzheimer’s dementia or other amyloid plaque-related diseases.

From the CDC’s website - a deeply concerning statistic.

Among US adults aged 18 years or older, estimates for 2017–2020 were:

38.0% of all US adults had prediabetes, based on their fasting glucose or A1C level. This means your blood sugar levels are elevated but not enough to be Type 2 diabetes- if not addressed through lifestyle and diet, prediabetes can progress to type 2 diabetes.

Dramatically reduce your chances of getting Alzheimer’s disease by getting a good night’s sleep.

The role between sleep cycles and the glymphatic system

Sleep cycles

When you sleep, you cycle through two phases of sleep: rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM sleep. The cycle starts over every 80 to 100 minutes. Usually, there are four to six cycles per night.

N 1. The transition between wakefulness and sleep. This transition lasts between one and seven minutes.

N 2. heart rate and body temperature decrease. Consolidation of memory and the ability to recall dreams occurs during this phase.

N 3. This is called deep sleep or slow-wave sleep, after a particular pattern that appears in measurements of brain activity. You usually spend more time in this stage early in the night. Memory consolidation continues, and hormones to aid in appetite control are released. In addition, the glymphatic system does most of its work, clearing amyloid plaque and other toxins during this cycle.

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep

During REM sleep, your eyes twitch and your brain is active. Brain activity measured during REM sleep is similar to your brain’s activity during waking hours. Dreaming usually happens during REM sleep. Newborns spend more time in REM sleep than older adults.

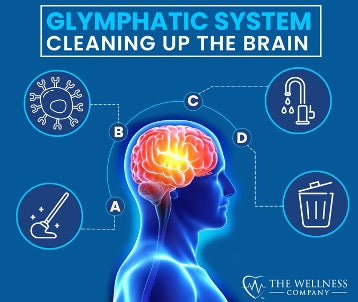

The role of the glymphatic system during sleep and how it relates to Alzheimer’s

The glymphatic system carries lymphatic fluid from the meningeal space into the brain through a series of vessels. In this way, it is comparable to the lymphatic system (the lymphatic system comprises the rest of the body.) It clears, cleans, and replenishes the brain through a network of lymphatic channels during sleep. Metabolic waste, such as amyloid plaque is removed, which in turn aids in nerve regeneration. It constantly filters toxins from the brain during the N3 cycle. The glymphatic system is mostly inactive when awake. (3)

(more than 90% of glymphatic activity takes place in the N3 (slow wave) sleep phase)

- During the N3 sleep phase, healthy brain cells mop up damaged cells and proteins, through a process called “autophagy” (self-eating”)

- From there, brain neurons coordinate electrical pulsations called “slow oscillatory neuronal activity” to further assist in clearing damaged cells, proteins, and amyloid plaque from the brain.

- Further activation during the N3 sleep phase allows fresh cerebrospinal fluid to enter the brain cavity, oxygenating and providing nutrients for the brain.

- The waste is collected in the cerebrospinal fluid and flushed into the lymphatic system where the body can expel the plaque, toxins, and other damaging metabolites.

A good night’s sleep is key to aiding your body in naturally removing the plaque.

Even with avoiding caffeine at night, limiting screen time before bedtime, not exercising right before bed, and avoiding snacks before bedtime, you may still have trouble falling asleep.

That’s where our Restful Sleep Formula can help

It combines:

- Passionflower to relax and promote an easy start to your sleep routine.

- Rafuma Leaf stabilizes the mind and prepares it for restful sleep.

- Kava mitigates the impacts of stress as you wind down.

- Chamomile for its time-tested properties of providing a gentle calming effect on the brain and body.

- Valerian Root to help reduce anxiety.

- Ashwagandha Root to help regulate the negative impacts of daily stress on your immune system.

To naturally manage amyloid plaque, our Spike formula contains proven, research backed ingredients, such as

From Dr. McCullough’s Base Spike Detox Trio protocol, add

for even more research-backed amyloid plaque-clearing protection, try

Our Vitamin D may help clear amyloid plaques

References

1.Nicolas G. Bazan. (2021). Amyloid Plaque. Retrieved from Science Direct: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/amyloid-plaque

- Masashi Tanaka. (2022, March 23). Alzheimer’s Disease as Type 3 Diabetes: Common Pathophysiological Mechanisms between Alzheimer’s Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. Retrieved from PubMed Central: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8910482/

- Jessen, N. A., Munk, A. S., Lundgaard, I., & Nedergaard, M. (2015). The Glymphatic System: A Beginner's Guide. Neurochemical research, 40(12), 2583–2599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-015-1581-6

- Sreekanth Sreekumaran, A. T. (2021). Chapter 14- Recent developments and new potentials for neuroregeneration. Academic Press.

Written by Brooke Lounsbury